Dr. Carolin Gluchowski

University of Hamburg

When we speak about the “advent of print,” it is still tempting to imagine a clean break: on one side the quiet scriptorium, on the other the noisy printing shop. Classic narratives by Lucien Febvre, Henri-Jean Martin and Elizabeth Eisenstein encouraged this view; subsequent scholarship, notably Adrian Johns’s, has shown how deeply misleading it can be. The Cistercian nuns of Kloster Medingen, near Lüneburg in northern Germany, offer a vivid case study of why this simple rupture does not hold. Their surviving books show that manuscript and print did not replace one another in a straightforward sequence. Instead, they overlapped, interacted and were creatively combined across what we might call Medingen’s “long fifteenth century,” c. 1400–1550.

In this post, I sketch how the Medingen nuns navigated this evolving media landscape. I introduce the convent and its manuscript corpus, outline its connections to the print hub of Lübeck, and highlight a genre at the heart of this story: the hybrid liturgical–devotional prayer book often labelled Orationale. I then ask how these books, though produced in an enclosed convent, participated in wider devotional “publics” in late medieval and early modern Central Europe⸺a question that resonates with the aims of the COST Action Print Culture and Public Spheres in Central Europe, 1500–1800 (CA23137).

Kloster Medingen and the Lüneburg Women’s Convents

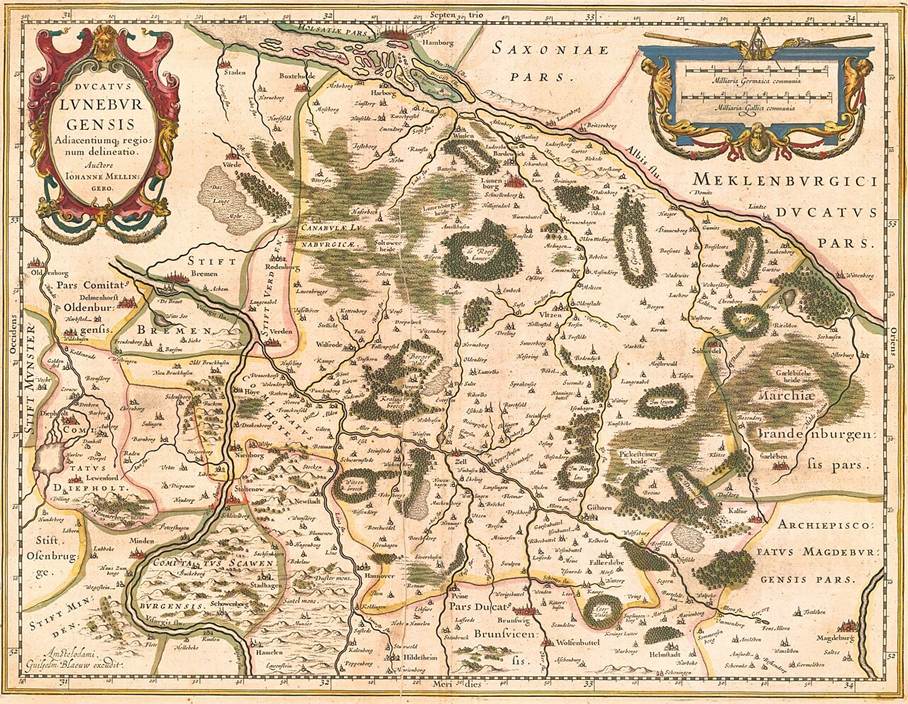

Figure 1: Map of the Principality of Lüneburg by Willem and Joan Blaeu (1645). The locations of the convents and collegiate foundations are marked with small cross symbols. The Lüneburg women’s convents form a loose ring around the town of Lüneburg, stretching along the Ilmenau river and out into the heathland to the south and east of the city. © Wikipedia.

Kloster Medingen is part of a compact cluster of women’s houses around Lüneburg: the Benedictine convents of Ebstorf, Lüne and Walsrode, and the Cistercian convents of Wienhausen, Isenhagen and Medingen (fig. 1). These so-called “Lüneburg women’s convents” were closely connected to one another, to regional noble families and, above all, to Lüneburg’s urban patriciate. Together they formed an unusually dense and well-documented constellation of women’s religious communities, now being reconstructed in the project The Nuns’ Networks (Henrike Lähnemann, Eva Schlotheuber).

Medingen originated as a thirteenth-century foundation and settled at its current site, south of Lüneburg, in the fourteenth century. Two major reform movements shaped its later history. In the fifteenth century, Observant reform⸺linked to the devotio moderna and the Windesheim and Bursfelde congregations⸺introduced stricter enclosure, intensified liturgy and more regular communal observance. Medingen actively prepared for this reform and, under reform Provost Tilemann von Bavenstedt, embraced it in 1479.

In the sixteenth century, the Lutheran Reformation posed a very different kind of challenge. From 1524 onwards, territorial rulers such as Duke Ernst the Confessor sought to seize control of the convents’ resources and to transform them into Lutheran women’s foundations. Medingen resisted for decades in what later tradition labelled the “Medingen nuns’ war”. Only in 1554 did Abbess Margarete Stöterogge publicly conform to Lutheran practice. Throughout these upheavals, books remained central: they structured the nuns’ devotional lives and mediated their carefully regulated contacts with the world beyond the cloister.

Prayer Books from Kloster Medingen

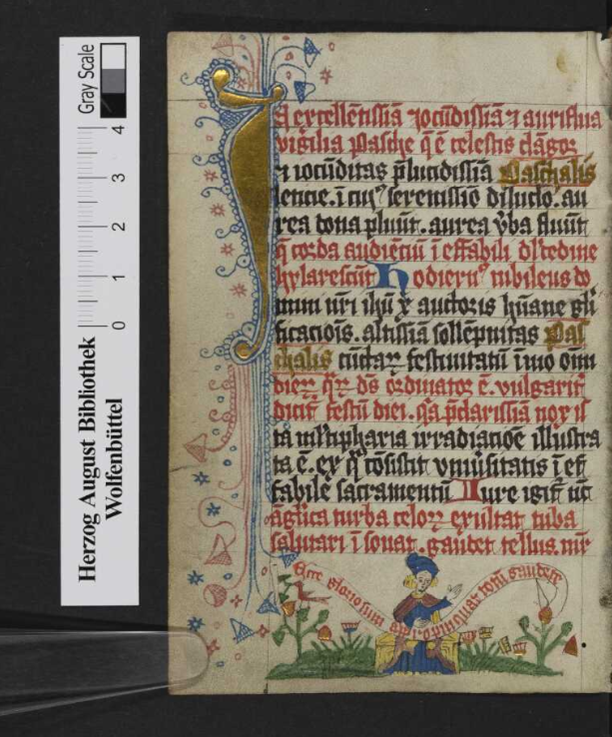

Figure 2: Hildesheim, Dombibliothek, J 29, fol. 1v. Opening page of the Easter prayer book completed in 1478 by the Medingen nun Winheid von Winsen. The prayer book is carefully decorated throughout in the distinctive, well-recognisable Medingen house style. © Dombibliothek Hildesheim.

Throughout these processes, books played a central role. Hand-written manuscripts and, later, printed works not only structured the nuns’ prayer life, but also mediated their carefully regulated contacts with the world beyond the cloister walls. Among the Lüneburg Women’s Convents, Medingen stands out for the size and coherence of its surviving manuscript corpus. The majority of surviving manuscripts are small personal prayer books on parchment and paper, often lavishly decorated despite their modest format (fig. 2). They are characteristically bilingual, combining Latin liturgical formulae with Middle Low German prayers, paraphrases and meditations. Because the Medingen library was largely destroyed, the convent’s manuscripts are now dispersed across libraries in Germany, Denmark, the United Kingdom, the United States and beyond—and none remain on site.

Most were produced between the early fifteenth and the mid-sixteenth century, making Medingen one of the best-documented monastic book corpora in northern Germany and a particularly rich source for the study of women’s devotion. The span covered by these books ⸺from an Easter prayer book completed in 1408 by the nun and later prioress Cecilia de Monte, through to the decades after the Lutheran Reformation⸺constitutes Medingen’s “long fifteenth century.”

From an early stage, such books circulated beyond the convent walls: some were gifts for relatives or patrons, others perhaps left the convent during the Reformation. That dispersal ⸺and the devastating fire of 1781 which destroyed much of Medingen’s library⸺means that we now encounter Medingen’s books mainly in external collections. Yet taken together, they allow us to follow how a single women’s community negotiated devotional, institutional and media change across 150 years.

Crucially, the period of Medingen’s most intense manuscript production overlaps almost exactly with the spread of print in northern Germany. Printed books were circulating in the region by the later fifteenth century, yet the nuns continued to copy, revise and rework manuscripts well into the sixteenth. Many volumes show multiple layers of later additions and corrections. Manuscript and print, in other words, coexisted and interacted, rather than simply succeeding one another.

Lübeck as a Printing Hub, Medingen as Reader

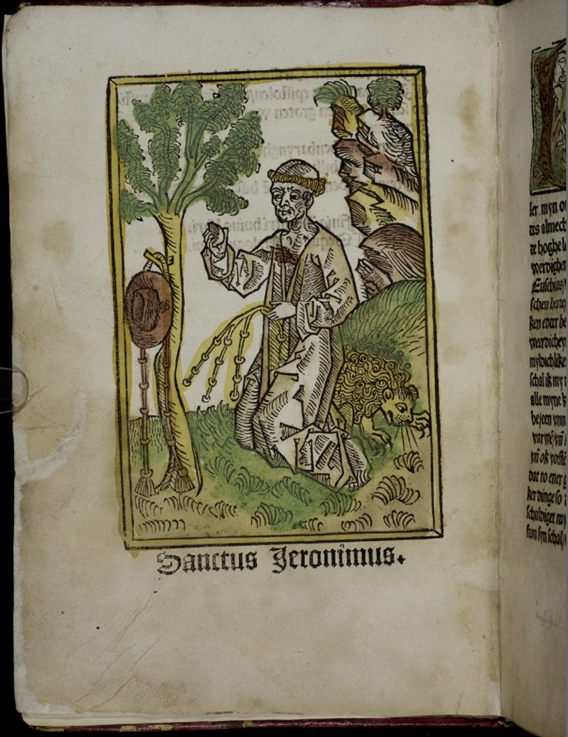

Figure 3: Göttingen, Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek, 8 Cod Ms. theol. 204, 2v. The miniatures in the print are partly illuminated, maybe by the nuns themselves? © SUB Göttingen.

To understand Medingen’s place in this media landscape, we need to look to Lübeck. From the 1470s, Lübeck developed into the leading printing centre of the Baltic. Lucas Brandis set up the city’s first press around 1473; by 1500 he had been joined by several other printers, together producing more than 300 editions. Over forty per cent of this output was in Middle Low German, and most titles were religious: psalters, saints’ lives, sermons, devotional treatises and, later, reforming works.

Medingen lay well within the orbit of this print market. The Lüneburg convents were integrated into Hanseatic trade routes; their patrons, confessors and suppliers moved between markets and ports. Through these networks, the nuns accessed urban booksellers as well as travelling clergy and reforming provosts who brought books with them.

Although the Medingen library was largely destroyed, a few traces reveal this engagement with print. A now-lost miscellany once combined a 1474 Mainz edition of Johannes de Turrecremata’s psalter commentary, printed by Peter Schöffer, with a manuscript (fig. 3). An ownership inscription recorded that Provost Tilemann von Bavenstedt had bought the book and given it to the nuns “for the salutary progress of the chapter’s reform.” Here, a demanding Latin commentary⸺rather than a simple vernacular tract⸺encapsulated both the authority of the new technology and a specific theological programme for the reformed convent.

At the other end of the spectrum, a small miscellany in Göttingen (8° Cod. Ms. theol. 204) combines a Lübeck incunable⸺a Middle Low German life of St Jerome printed by Bartholomäus Ghotan⸺with later handwritten devotional texts by and for the Medingen nuns. In this one codex, print and manuscript are literally bound together. Such hybrids show how printed works were integrated into local reading practices and adapted to convent needs.

Visual Dialogue: Medingen Psalters and Lucas Brandis

The interaction of manuscript and print is particularly visible in illumination. Around 1473/74, Lucas Brandis produced one of the earliest substantial Middle Low German printed psalters in Lübeck, a quarto edition whose layout and woodcut decoration deliberately evoke a luxury manuscript (fig. 4; GW M36237, ISTC ip01073800.). It was clearly aimed at a devotional market familiar with vernacular psalters in codex form, including religious women and devout laypeople.

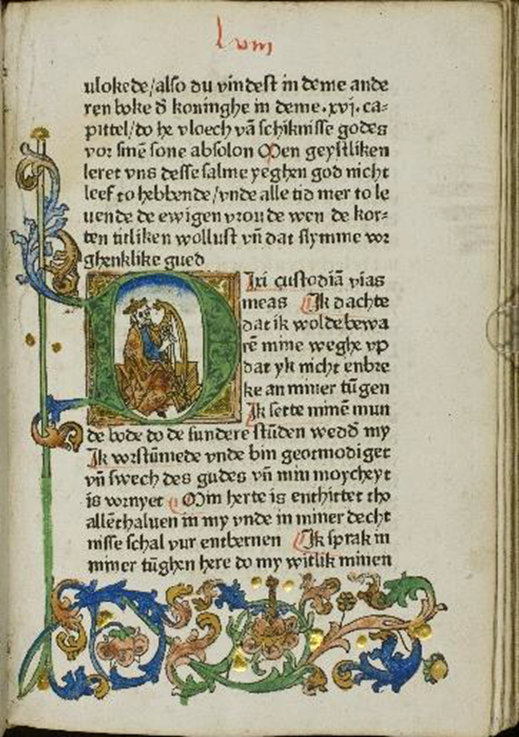

Figure 4: Hamburg, Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek, Scrin 84b, 67r: Middle Low German psalter, [Lübeck: Lukas Brandis, c. 1474]. © SUB Hamburg.

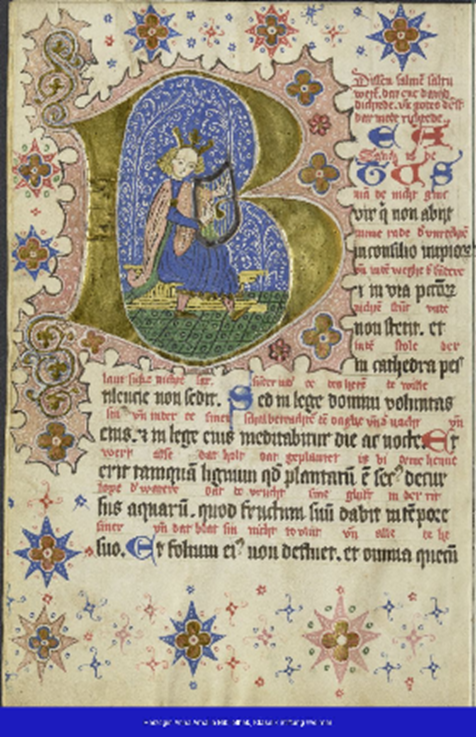

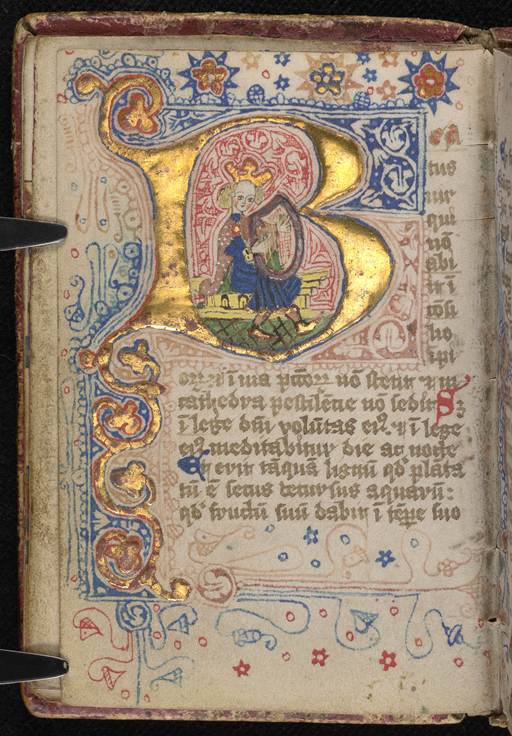

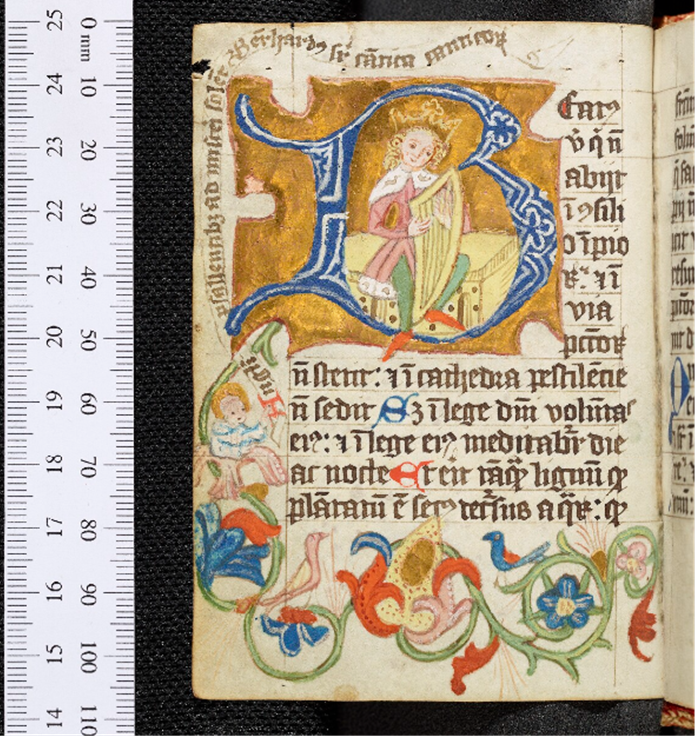

Several Medingen psalters—notably those now in Oxford (MS. Don. e. 248,) and Weimar (Fol. 35)—display striking visual affinities with Brandis’ edition: similar schemes of decorated initials, comparable key scenes (David, Christ, favourite saints), and related approaches to framing and marginal ornament (figs. 5–7). Someone in or near the Medingen scriptorium seems to have known Brandis’ psalter and treated it as a visual point of reference.

Figure 5: Weimar, Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek, Fol. 35, 7v. A rare fifteenth-century interlinear translation of the psalter from Latin into Middle Low German; the initial shows King David playing the harp. Although its visual language is closely related to Lucas Brandis’s vernacular printed psalter, the translation itself is independent and not identical to the print. © HAAB Weimar.

Figure 6: Williamstown, Chapin Library, Mss 008, 15v. This Latin psalter, recently attributed to Medingen, is the most lavishly decorated manuscript in the entire corpus. The source of its decoration program remains unclear, and it is still uncertain where the model for this elaborate design originated. © Chapin Library Williamtown.

Figure 7: Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS. Don. e. 248, 20v. This psalter belonged to the Medingen nuns Margarete Hopes and was heavily reworked in the context of the Reformation. © Bodleian Library Oxford.

Rather than assuming a simple one-way influence, it may be more accurate to speak of a visual dialogue. Both the Lübeck woodcuts and the Medingen miniatures draw on a shared north German iconographic repertoire. Manuscript and print borrow from and sharpen one another, and the nuns’ imaginative world is shaped by both established manuscript patterns and by compositional possibilities crystallised in print.

Hybrid Pages: The Hannover Easter Prayer Book

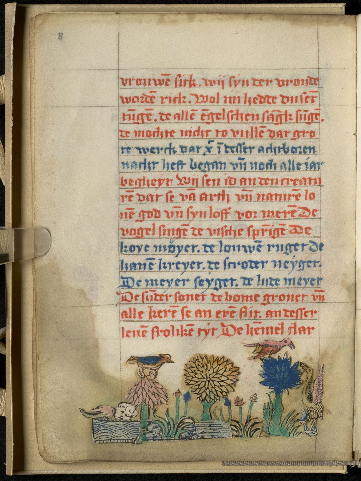

Figure 8: Hannover, Landesbibliothek, MS. I 74, p. 8. This heavily reworked Easter prayer book incorporates, in its margins, cut-out snippets from a hitherto unidentified printed book. © Landesbibliothek Hannover.

An especially vivid example of media hybridity is an Easter Orationale from Medingen, now in Hannover (Ms. I 74). This small prayer book for the Easter octave, written in Latin and Middle Low German and dated to the second third of the sixteenth century, continues the Medingen tradition of personalised prayer books⸺but with a twist.

Instead of relying solely on painted illumination, the manuscript incorporates cut-out printed snippets. Small fragments from a (so far unidentified) printed book have been carefully trimmed and pasted into the margins of the handwritten pages. Some function as miniature framed images, others as ornamental bands. Manuscript text and printed image are visibly juxtaposed on the same page.

Here, print is treated as raw material for ongoing manuscript production. The main text remains handwritten and flexible, with rubrics, corrections and later additions; printed woodcuts are literally collaged into this framework. The book also mixes parchment and paper and shows evidence of later rebinding and repairs. It is a palimpsest in which the gradual, overlapping nature of the transition between manuscript and print becomes materially legible.

What Is an Orationale? Between Standardisation and Personalisation

Most Medingen prayer books, like the aforementioned Easter prayer book in Hannover, belong to a genre usually labelled ‘Orationale.’ Comparable books survive from other north German women’s houses such as Wienhausen, Lüne, Ebstorf, Isenhagen and Walsrode. They combine Latin liturgy with Middle Low German prayers, saints’ offices and meditative expansions. At their core, the Orationalia adopt the fixed Latin framework of office and Mass⸺chants, readings, collects, rubrics and feast cycles, typically following the diocesan liturgy. Around this backbone, the nuns weave Middle Low German translations, paraphrases and original prayers. Liturgical formulae become starting points for extended vernacular meditation. The Orationale thus links the standardising force of diocesan liturgy with a highly flexible, often very personal language of devotion.

This unsettles the familiar opposition between “standardising” print and “individualised” manuscript. On the one hand, the Orationalia encode a highly standardised vision of convent life: they prescribe how the Easter liturgy should be celebrated, how processions should run, how daily and yearly rhythms of prayer should be structured. In a reformed convent, such books were powerful tools of uniform observance. On the other hand, each Orationale is also deeply personal. Text selection, arrangement and decoration reflect a particular nun’s devotional profile; names, arms and dedicatory verses tie books to specific families; marginal additions reveal how successive generations reworked inherited volumes. The material form of the manuscript – with its blank spaces, margins and insertable leaves – makes such ongoing negotiation possible.

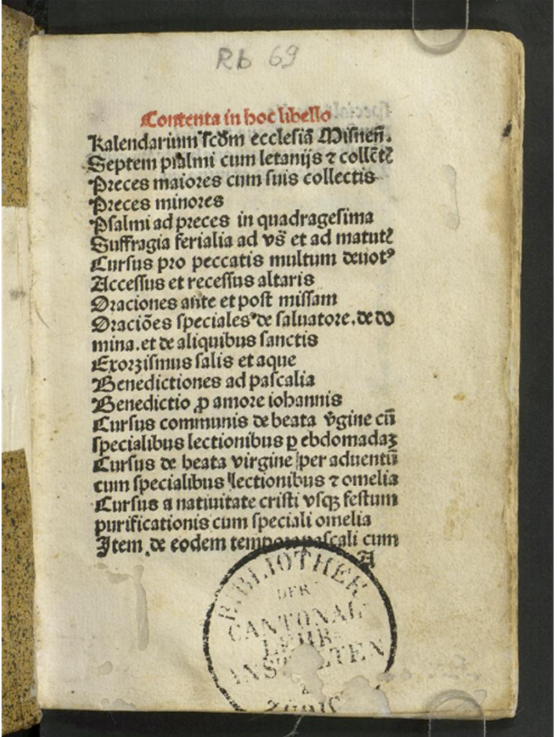

Figure 9: Zürich, Zentralbibliothek, Rb 69: Horae. Orationale secundum ecclesiam Misnensem, [Leipzig: Konrad Kachelofen, c. 1495]. Unfortunately, the title page of this print is missing. © Zentralbibliothek Zürich.

Beyond the Medingen manuscripts, there are also early printed Orationalia that show the genre’s move into print. One is the Horae. Orationale secundum ecclesiam Misnensem (Meißen), printed in Leipzig by Konrad Kachelofen around 1495 (fig. 9, GW 12956; ISTC ih00348050). A second case is the Lübeck incunable Horae. Orationale diversa continens officia, produced in 1489 in the so-called Mohnkopfdruckerei of Hans van Ghetelen (GW 12961; ISTC ih00435150); the only known surviving copy is held in Hannover in the Kestner-Museum.

Despite their importance, there is still no sustained study of the Orationale as a genre, or of its transmission across manuscript and print. This gap is significant, because Orationalia sit precisely at the intersection of convent liturgy and individual devotion, and thus make the oscillation between standardisation and personalisation particularly visible.

Devotional “Publics” and the Reach of Convent Books

From the perspective of the COST Action Print Cultures and Public Spheres, Medingen invites us to rethink how monastic books participate in wider devotional “publics.” On the face of it, a medieval women’s convent is the opposite of a public sphere: an enclosed space, liturgy behind walls, regulated access.

Yet, Medingen’s Orationalia were not confined to the choir. Many were made as gifts for women outside the convent: urban patricians, noble ladies, or sisters entering other houses. These books carried Medingen’s particular style of devotion – its images, saints’ cults and temporal rhythms – into lay and semi-lay environments. They contributed to a regional devotional conversation that extended beyond the cloister but retained a monastic imprint.

Print intensified and broadened that conversation. Lübeck books such as Brandis’ psalter or Ghotan’s saints’ lives addressed urban readers and the devout middle classes as much as convents. When such books entered Medingen, the nuns joined a wider reading community. When they annotated, adapted and physically combined printed and handwritten materials, they fed monastic perspectives back into the pool of shared religious texts.

By the early sixteenth century, this pool increasingly included explicitly reforming works. Medingen and its neighbours were targets of reforming propaganda and participants in the emerging “Reformation public sphere.” Their continued copying of some texts, quiet dropping of others and subtle marginal adjustments reflect a negotiated engagement with this new environment.

Outlook: Towards an Integrated Media History of Medingen

Research on Medingen has so far concentrated, necessarily, on the manuscripts: cataloguing, editing and contextualising these complex prayer books. The next step is to bring manuscript and print into a single analytical frame.

This means comparing Medingen illumination with printed models such as Brandis’ psalter; studying hybrid objects like the Göttingen bookand the Hannover Orationale in detail; and mapping the circulation of books between Lübeck, Lüneburg and the convents. Conceptually, it also means moving away from a simple “before and after print” narrative.

At Medingen, there is no abrupt media revolution. Instead, we see a long period in which handwritten and printed books coexist, interact and reshape one another. The nuns use the flexibility of the manuscript codex to adjust their devotional life over generations, while printed works bring new authorities and visual patterns into the convent.

Seen from this angle, the Medingen nuns were not merely passive recipients of new technology. In their small prayer books and hybrid Orationalia, they actively explored how manuscript and print could work together in the service of devotion – and, in the process, helped to define the contours of a new devotional public extending well beyond their cloister walls.