11 February 2026 – International Day of Women and Girls in Science

By Carolin Gluchowski, Gender Equality and Inclusiveness (GEI), Officer and Valentyna Bochkovska

PCPSCE – Print Culture and Public Spheres in Central Europe (1500–1800)

On the International Day of Women and Girls in Science, marked each year on 11 February by the United Nations and UNESCO, we are invited to reflect not only on contemporary efforts to support women in research, but also on the longer histories that have shaped how knowledge is produced, circulated, and sustained. Women’s contributions to these knowledge infrastructures extend back centuries, even when their work has been rendered invisible, attributed to others, or treated as exceptional rather than structural.

Today, science and scholarship depend on strong mentoring networks, inclusive research environments, leadership opportunities, and funding structures that recognise care responsibilities and uneven access to resources. Within the PCPSCE COST Action, we are committed to fostering such inclusive practices: supporting early-career researchers through mentoring and exchange, ensuring gender-balanced panels and working groups, and advocating for care-aware funding that lowers barriers to participation. These measures are not merely procedural. They are foundational to building research cultures in which women can participate fully—as scholars, collaborators, and leaders.

At the same time, this moment of reflection invites us to look beyond the present. By situating contemporary initiatives within a longer historical perspective, we can better understand how women have long shaped the production and circulation of knowledge—and why recognising these contributions matters for the future of inclusive research cultures.

Women Printers in the Early Modern World: Agents of Knowledge Production

Long before modern laboratories and research institutes, women played a central role in sustaining Europe’s systems of knowledge. In the early modern period, print shops and publishing networks formed the backbone of education, religious life, and public debate. Far from marginal figures, women were active participants in the material, economic, and intellectual work of print.

A well-documented example is the Parisian printer Yolande Bonhomme (c. 1490–1557). After her husband’s death in 1522, she assumed control of the family press on the Rue Saint-Jacques, a major centre of scholarly and devotional publishing. Working for institutional patrons such as the University of Paris and the Catholic Church, Bonhomme produced books of hours and liturgical texts and, in 1526, became the first known woman to publish a Bible. With between 136 and 200 surviving or attributed editions, she ranked among the most productive printers of her generation, even as her reliance on her husband’s name in colophons long obscured her authorship.

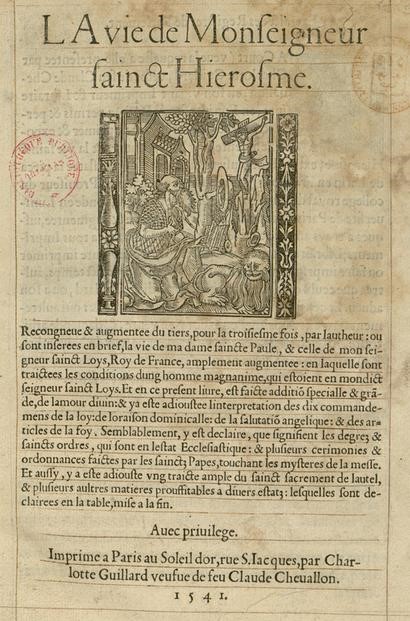

Fig. 1: Colophon from a devotional printed by Yolande Bonhomme. SMU Libraries, Bridwell Library Special Collections, BRB0456.

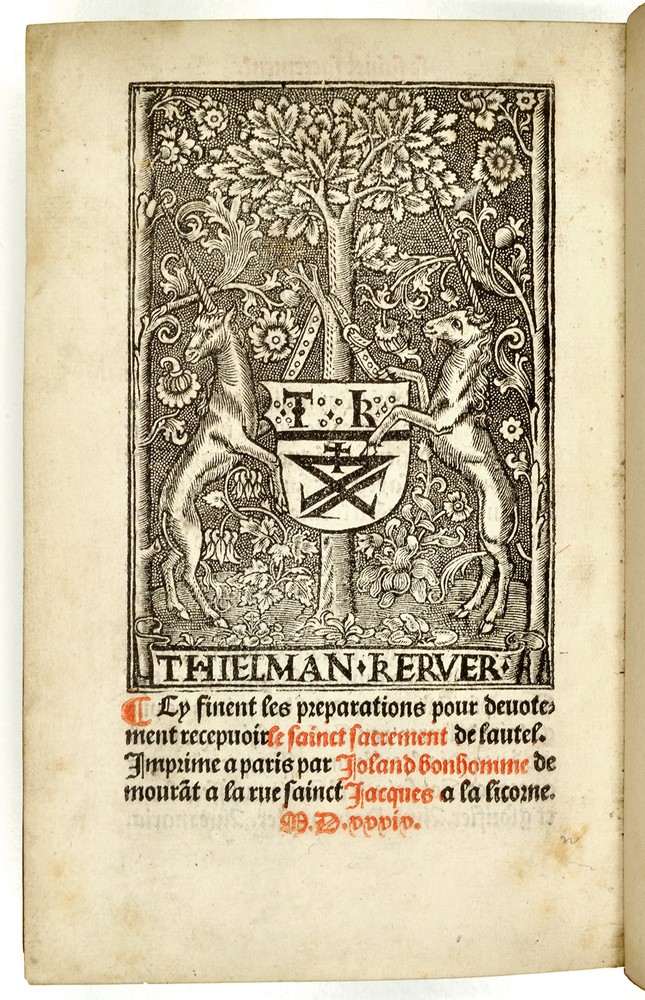

Bonhomme’s career reflects a broader European pattern. In Paris, Charlotte Guillard (c. 1480–1557) ran one of the most influential scholarly presses of the sixteenth century, specialising in legal and humanist works and shaping material standards through direct negotiation with papermakers’ guilds. In the Holy Roman Empire, Magdalena Morhart managed a major press in Tübingen, producing hundreds of titles for university and territorial authorities. In England, Alice Broad maintained York’s only printing house during the political instability of the mid-seventeenth century, ensuring the continuity of local print production.

Fig. 2: Title page from a work printed by Charlotte Guillard, Paris, 1541. Bibliothèque municipale d’Orléans, Rés. E 1410.

Women Printers in Ukrain

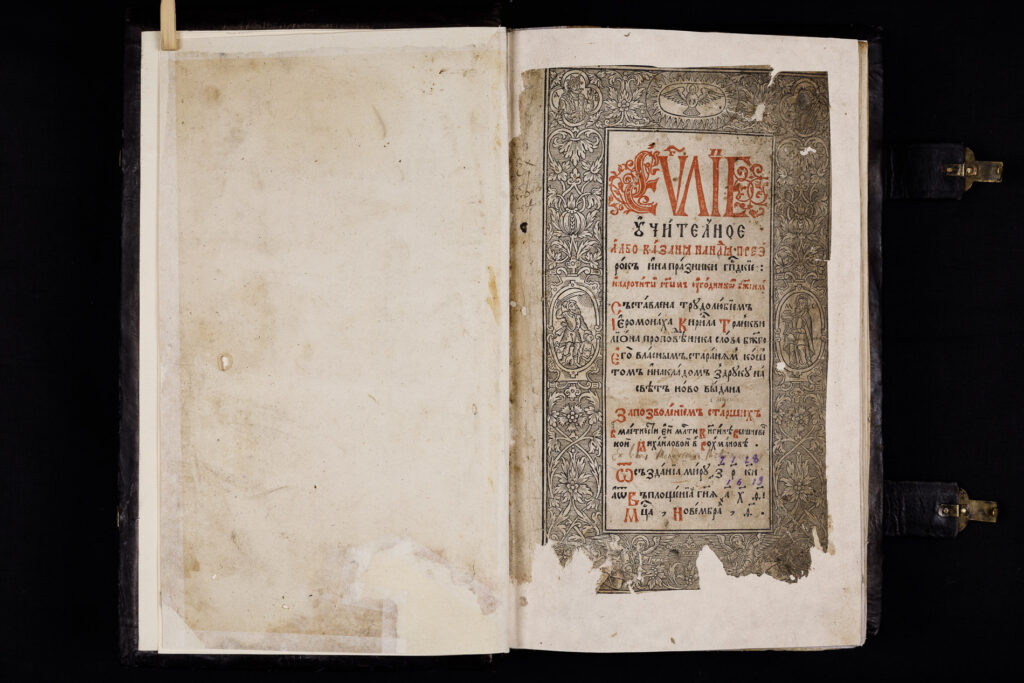

Recent research by Valentyna Bochkovska helps situate the first women in Ukrainian printing within this wider landscape. She shows that from the late sixteenth century, book production in Ukrainian lands developed as a decentralised and socially embedded practice, supported by private printers, brotherhoods, churches, and urban communities rather than a single state authority. Within this environment, women most often entered printing through family workshops, acting as widows, heirs, or partners, even when their names were absent from title pages.

But we know their names from the prefaces of books and archive documents. For example, Princess Sofia Chortoryiska opened a Printing Shop on her estate in the village of Rokhmaniv in Volhynia (1618-1619). She was a well-educated woman and engaded in preparing books to publication, translated the Holy Scriptures (as well as the Gospels and the Apostolic Discourses) from Greek into Slavic (Old Ukrainian). We read this testimony from the author-printer Cyril Tranquillon Stavrovets in the preface to book Gospel Homiliary: «Translated from Greek into Slovenian through the efforts, craftsmanship, and expense of Her Grace Princess Sofia Chortoryiska, sister of Your Princely Grace.»

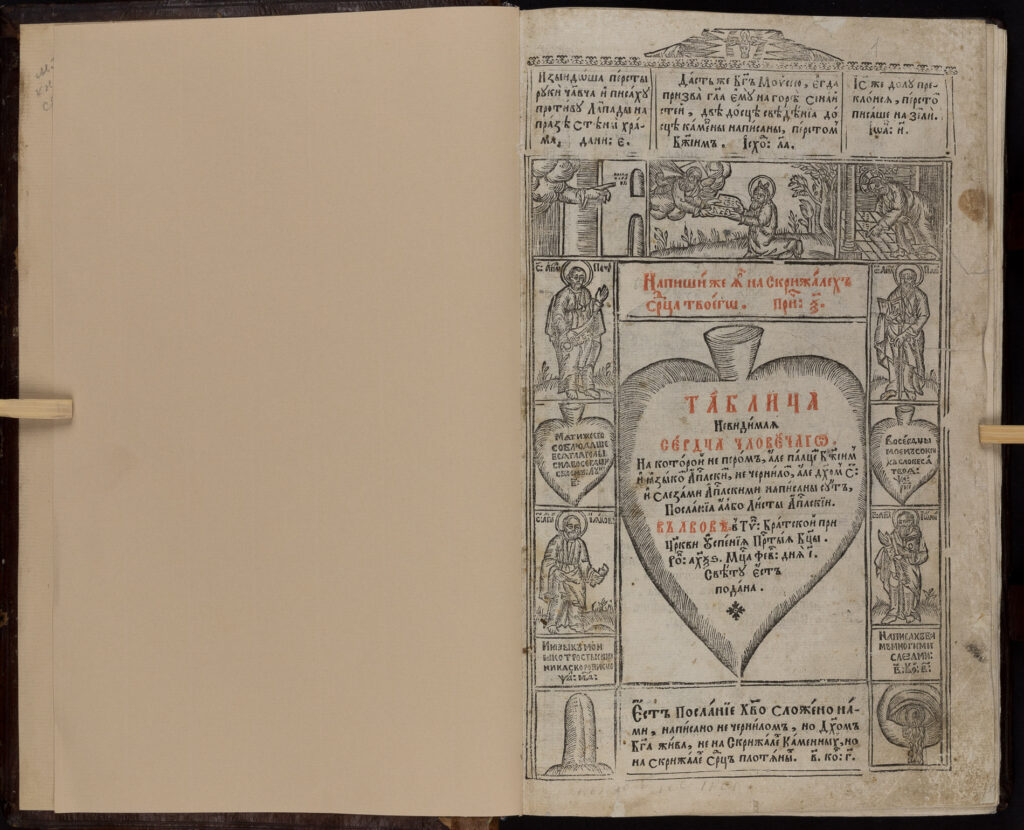

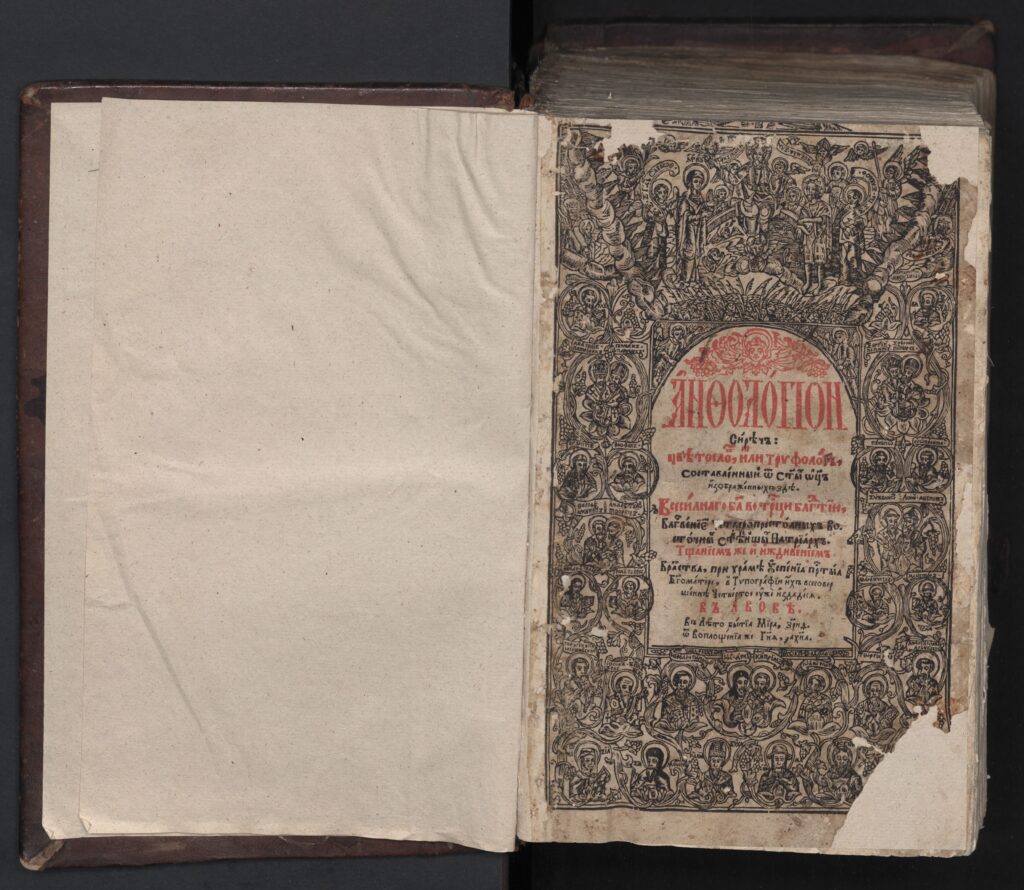

The archive documents preserve for us the name of the first Ukrainian woman printer – Kulchytskaor«Dmytrova’s printer» (wife of Dmytro). She worked in the Printing House of L’viv Stavropigia Assumption Brotherhood during 1662-1664. We know the name of the very successful bookseller of L’viv Stavropigia Assumption Brotherhood «Nastasia Lyashkivska» (1676-1680). Anastasia Lyaskovskaya personally engaged in book trading, obtained books for sale, and kept records for financial reporting to the Brotherhood. She had enormous sums of money at her disposal and bore great responsibility for the sale of books, and she coped with this work successfully. The largest number of copies of books for sale was issued to Anastasia Lyaskovskaya in 1679 for the sum of 9,450 zlotysand 20 groszy, and the smallest in 1678 for the sum of 3,980 zlotys and 7 groszy.The breadth of output—from liturgical books to primers and educational texts—underscores that Ukrainian printing functioned as a broad knowledge infrastructure rather than a narrowly ecclesiastical enterprise.

Fig. 3: List of books for sale by Anastasia Lyaskovska – Apostol. Lviv, 1666.

Fig. 4: List of books for sale by Anastasia Lyaskovska – Apostol. Lviv, 1666.

Fig. 5: List of books for sale by Anastasia Lyaskovska Trefologion. Lviv, 1651.

As initiatives such as the Women Printers Project demonstrate, these women were not isolated exceptions. Across Europe, women printers formed part of durable professional lineages, collaborating with authors, scholars, universities, churches, and civic authorities; negotiating labour, materials, and markets; and shaping decisions about what was printed and how it circulated. Their print shops operated as the research infrastructures of their time—sites where knowledge was selected, standardised, and debated. From this perspective, women’s labour was not peripheral to early modern public spheres, but constitutive of them.

Bridging Past and Present: Why History Matters for Inclusive Futures

This historical perspective has clear contemporary relevance. Just as early modern print networks combined opportunity with constraint, today’s academic systems can either reproduce exclusion or actively foster participation. Despite increasing levels of participation, women remain under-represented in senior positions and leadership roles across many fields—reminding us that equality is not a finished project, but an ongoing process shaped by structures, cultures, and institutional choices.

Within PCPSCE, our work on gender and inclusiveness is consciously situated within this longer history. We seek to make research cultures more equitable by supporting mentoring and peer exchange, promoting inclusive and gender-balanced panels, encouraging leadership opportunities, and advocating for care-aware funding practices that reflect the realities of academic life. These efforts align closely with the aims of the International Day of Women and Girls in Science, which UNESCO’s 2026 celebrations frame as a call to advance gender equality across all fields of knowledge.

By bringing together the histories of women who shaped early modern print culture with present-day research practices, we gain a richer understanding of what it means to build inclusive knowledge infrastructures. Past and present alike remind us that when women are able to participate fully—as printers, researchers, educators, and leaders—public spheres become more dynamic, research cultures more resilient, and our shared capacity to produce and circulate knowledge significantly stronger.

Literature

Baker, Catherine A., and Rebecca M Chung, eds. Making Impressions : Women in Printing and Publishing. Chelsea, Michigan: The Legacy Press, 2020.

Beech, Beatrice. Yolande Bonhomme: A Renaissance Printer. In: Medieval Prosopography, 6, 2, 1985, p. 79–100

Broomhall, Susan. Women and the Book Trade in Sixteenth-Century France. Women and Gender in the Early Modern World. Aldershot, England: Burlington, VT, 2002.

Hudak, Leona M. Early American Women Printers and Publishers,1639-1820. Metuchen, N.J.: Metuchen, N.J. : Scarecrow Press, 1978.

Sauer, Christine, ed. Frauen machen Druck! Nürnbergs Buchdruckerinnen der Frühen Neuzeit. Ausstellungskatalog der Stadtbibliothek Nürnberg 112. Nürnberg: Stadtbibliothek Nürnberg, 2023.