Dr Robert Tomczak

Research Associate, Department of Early Modern History, Czech Academy of Science

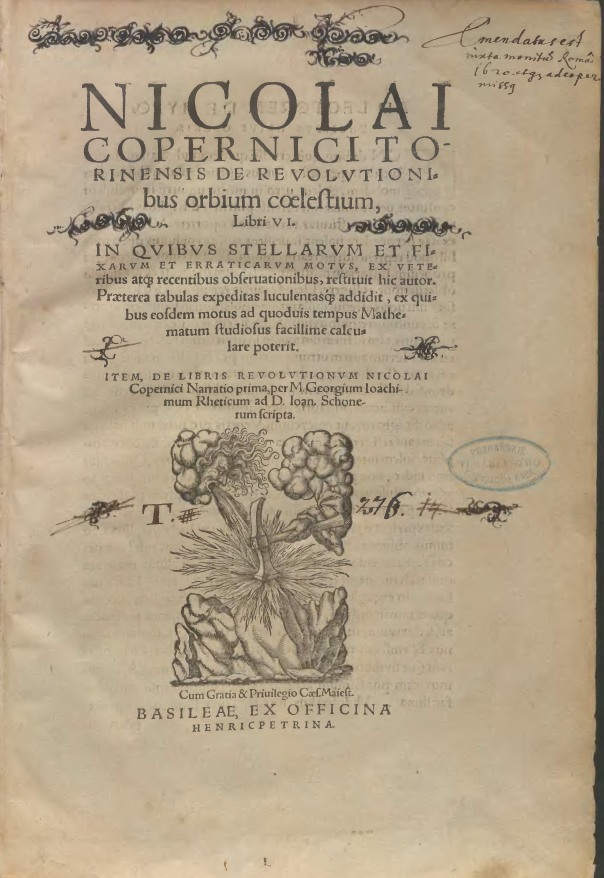

The history of Nicolaus Copernicus’s (1473–1543) De revolutionibus orbium coelestium

(1543) is not only a story of a scientific revolution but also of the control of the printed word

and of tensions between science and the Church. A copy of the second edition (Basel,

1566), preserved in the Library of the Poznań Society of Friends of Learning (PTPN),

provides a unique testimony to the censorship imposed on the work of the Toruń astronomer

in the seventeenth century.

Portrait of Copernicus (Jeremias Falck, 1644: Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, RP-P-OB-50.568, public domain)

Copernicus and His Work

Copernicus worked on his heliocentric theory for three decades, combining his duties as administrator of the Warmian cathedral chapter estates with astronomical research. The geocentric theory of Ptolemy—according to which the Earth remained at the center of the universe—was then an unquestionable paradigm. Copernicus placed the Sun at the center and argued that the Earth rotates both on its axis and around the Sun. His theories, completed around 1530, were not published until 1543, shortly before his death.

Although Copernicus’s mathematical and astronomical arguments initially circulated mainly among specialists, their consequences for philosophy and theology proved revolutionary.

Celestial map of the Copernican system (1660: Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, RP-P-AO-29-1-6, public domain)

On the Index

In 1616 the Congregation of the Holy Office declared heliocentric claims “absurd” and “heretical.” De revolutionibus was placed on the Index of Prohibited Books—with the proviso that it could circulate provided it was “corrected.” In May 1620, Rome issued a detailed instruction specifying which passages were to be altered or removed.

Owners of copies were obliged to make the prescribed changes in the text. Some scholars, such as Galileo (1564–1642), applied “simulated censorship,” striking through words with a thin line so that they remained legible. The PTPN copy, however, was censored with exceptional thoroughness.

A Censor’s Trace in Poznań

The book belonged to a Jesuit college and bears all the corrections required by the 1620 decree. On the title page, a note was added: Emendatus est iuxta monitum Romae 1620 atque adeo permissus—“Corrected in accordance with the decree from Rome in 1620 and therefore permitted for reading.”

Title page of Copernicus’ work (Library of the Poznań Society of Friends of Learning, 10617. III, public domain)

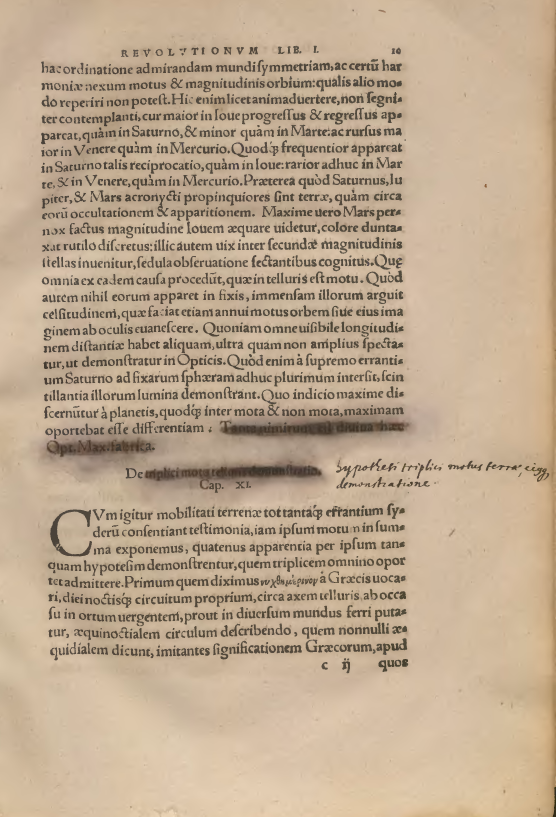

One example of intervention is the alteration of the title of a chapter on the Earth’s motions. Originally it read “Demonstration of the Threefold Motion of the Earth,” but after censorship it became “On the Hypothesis of the Threefold Motion of the Earth and Its Proof.” The difference is significant: instead of scientific certainty, only a “hypothesis” remained.

Likewise, the conclusion of the chapter containing the iconic heliocentric diagram was censored. Copernicus’s lofty phrase, “So indeed vast is this divine handiwork of the Best and Greatest Being,” was judged dangerous in connection with the following chapter and consequently removed.

Change of chapter title (Library of the Poznań Society of Friends of Learning, 10617. III, p. 10, public domain)

The Local Context of a Global Censorship

As Dr. Norbert Delestowicz, Director of the PTPN Library, emphasizes, this copy is an exceptional testimony to seventeenth-century censorship practice. While in Protestant countries or in more distant parts of Europe the Roman directives were often ignored, Catholic institutions—especially the Jesuits—observed them with great meticulousness.

The Poznań copy allows us today to trace mechanisms of print control and their practical application: from Roman instructions to handwritten corrections made by book owners. It also reminds us that the print culture of the early modern period was an arena of negotiation between science, authority, and religion.

Poznań Society of Friends of Learning Library (photograph by Robert T. Tomczak)

Legacy

Thanks to the research of Owen Gingerich (1930–2013), we know that at least 14 copies of De revolutionibus have survived in Poland. The PTPN collection contains as many as four editions of Copernicus’s work, including the 1543 first edition. Yet it is the Basel edition of 1566, censored by a seventeenth-century Jesuit hand, that provides a particularly striking testimony to the reception and the constraints that confronted this revolutionary theory.

Today De revolutionibus is part of the canon of world science. The Poznań copy, however, offers a different perspective on this history—as a story about the freedom and restrictions of print, about the power of ideas, and about how the scientific revolution first had to pass through the sieve of censorship.